Most people aren’t seriously thinking about fertility until they’re too old to do much about it, according to fertility researcher Emmalee Ford, whose work has recently been published in the journal Reproduction.

I sat down with Ford to have a fascinating chat on the very broad topic of fertility, hormones and birth control. I wanted her to tell me everything she knew.

It stems from personal interest. I became a better reader of my body and emotions after I ditched hormonal birth control at the age of 21 after three years on the pill. I read an enlightening book called Flow, The cultural story of Menstruation (by Elissa Stein and Susan Kim). I couldn’t believe there was so little I (and much of the world) understood about women’s bodies and hormones.

Frustratingly, all forms of non-hormonal birth control have a slightly higher failure rate, a risk I’m willing to take.

From the rise of fertility apps to the spike of artificial estrogen in the water supply, concerns about our hormones and our fertility are valid and rising. More articles than ever are being written about contraception, from Scientific American to The Guardian to The Washington Post and many more. The Cut recently published an article confirming that an average woman’s cycle is not 28 days, it’s 29.3, similar to the moon’s 29.5.

Reproduction

Our reproductive system is shrouded in mystery, Ford says.

“We don’t talk about people who are having abortions or miscarriages; it needs to be put in the spotlight. We don’t even talk about periods.”

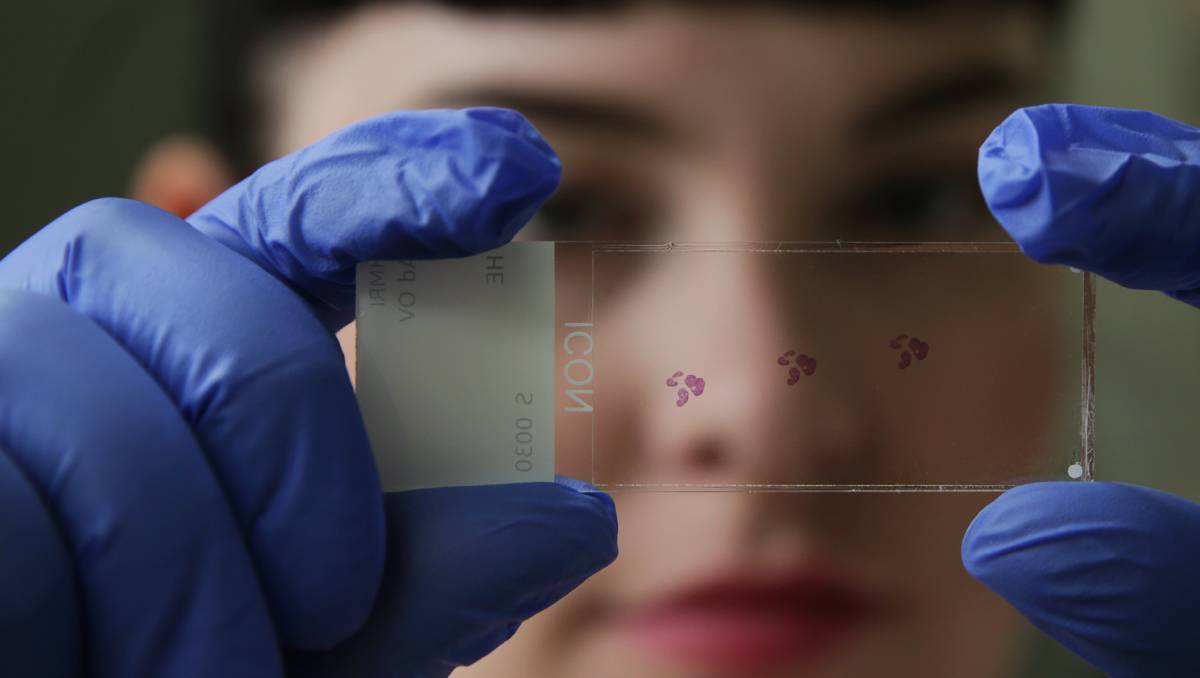

Ford is a PhD candidate at the University of Newcastle. She studies early fertility loss and accessibility to fertility information. She received her honours in male fertility. Her academic path started after she became fascinated in a reproductive science class.

“I just really like reproduction. What really got me was how everything has to line up so perfectly to produce a pregnancy,” she says.

As she says, during sex it’s pretty hard for the sperm to get to the egg. Sperm are made in the testes, then stored in the epididymis. Once ejaculated and exposed to the female reproductive track, their motility is hyper activated. Sperm have to follow several signals to get to the fallopian tubes, which isn’t easy. If or when they reach the fallopian tubes, there are thousands of microscopic hairs that beat the egg down, so the sperm has to navigate them. Of millions of sperm, only the fittest get there. (If the woman’s body isn’t ovulating, it’s even more hostile.)

Sperm can live in the body for up to a week, but during every intercourse there’s only a one in five chance for two fertile people to get pregnant. The egg can be fertilised, but it then has to implant into the wall of the uterus, so it has to go all the way down from the fallopian tubes.

“That’s a hurdle becoming more prevalent, with endometriosis being more common,” Ford says. Also, hormonal birth control masks and delays the symptoms of endometriosis, making it harder to be diagnosed.

It’s quite hard to get pregnant, and, yet, Ford says that if everyone used birth control perfectly, there would still be 200,000 unintended pregnancies a year.

Go with the flow?

Five million eggs are formed while a female baby is in utero. But, in her reproductive life, a woman ovulates only 400 times. During this time, the eggs are going through a continual process of growing or dying. The eggs of women on hormonal birth control just repeatedly die rather than get ovulated.

“They get broken down inside the ovary. If you are ovulating, only one is picked. Your body is trying to make sure any errors are destroyed, trying to make sure each one is the best one,” she says.

Hormonal birth control is made up of two hormones that mimic the state of a woman’s body if she was about to be pregnant: progesterone and estrogen (sometimes).

“It’s basically an empty cycle with no ovulation, it’s quite similar to what you would [naturally] be like. All the systems in your body that hormones control like bone density and body temperature [are the same], it’s just (altering) the surge that induces the egg to ovulate,” she says.

Hormones (real or synthetic) are responsible for PMS (premenstrual syndrome), and women need those to control other areas of their physiology.

I’ve been using an app to track my cycle and sex habits for years, but I started paying more attention as soon as I went off the pill. I experience surges of optimism and joy (and possibly more attention from others) when I’m ovulating. Then there’s rage and tears when I’m premenstrual.

Oddly, in the winter, I get my period more than in the summer.

When I travel overseas my period gets all out of whack. I tend to have sex more when I’m ovulating, terrifying but predictable.

When I first went off the pill, I had my period twice in the following year. My period didn’t become fairly regular until I got into my first serious relationship at 23.

It’s almost like my body relaxed and was like “now you’re physically ready to become a mother.”

Not all apps are equal

Ford and her colleagues are researching these fertility apps. They’re looking at the association between people who use reproductive health apps and their knowledge about fertility. They wanted to see if there was a difference in knowledge levels between those who did and didn’t use apps.

“We did find difference between the knowledge, but we only had six questions, and most people performed poorly. So we know that fertility knowledge is poor in women in Australia,” Ford says.

More and more articles are being published in Australia and around the world highlighting how inaccurate these apps are at predicting ovulation.

Ford will soon be reviewing menstrual cycle tracking apps in Australia, looking at normal and abnormal menstrual cycles and testing the apps

‘ functions, c

laims and accuracy of information.

I randomly downloaded my app based on a friend’s recommendation. Mine is called Glow and I like it because it’s easy to use and I can also track other things about myself with it: my weight, my mood, even my cervical mucus’ thickness.

“I think there needs to be regulation; they need to be explicit if they’re not verified,” she says of the apps. “I think it’s good because personalised information is really important, but we can’t just rely on something because it’s there.”

Earlier this year Cosmopolitan recommended the following apps for period tracking: Clue, Eve Tracker App, Flo Period & Ovulation, Period Diary, Ovia Fertility Period Tracker, Cycles and Dot.

The business of baby-making

This is all helpful information for anyone who doesn’t want to get pregnant, but what about people who do?

“Being in general good health is enough to make a difference,” she told me.

But in the western world, infertility is on the rise.

“One in six couples in Australia have infertility. That’s defined as a year of unproductive sex and no baby. Forty per cent of the time it’s (because of the) male 40 per cent of the time it’s female. Twenty per cent of the time it’s unknown,” she says. “Lifestyle factors like smoking, drinking and obesity can reduce fertility.”

She mentioned environmental exposure as well like plasticising agents and BPAS. Another is acrylamide, a chemical which forms in food when it’s fried.

“A combination of many things in small amounts chip away at someone’s reproductive capacity,” she says. “We’re finding that many things in our environment have effects that persist across generations.”

With women, age is the largest limiting factor in fertility, and the age of mothers is going up in Australia.

“If you’re over 35 it’s more difficult to get pregnant, and you’re more likely to lose a pregnancy,” Ford says. “It’s not that it’s impossible but there’s risk. You can get pregnant at any age, it’s the egg that is the issue.”

Many countries still have skyrocketing population rates as well, so some might argue ‘what’s the point in encouraging more population?’ But Ford believes researching fertility is not about making sure everyone has babies.

“It’s about making sure every life has the best start,” she says.

I could have talked to Ford all week about fertility, hormones and baby making. I hesitantly asked her what she thought about my aversion to hormonal birth control, knowing this causes eye rolls in certain circles.

“If you’ve been on (hormonal) birth control for years, it’s worth seeing the alternative,” Ford says. “I definitely think it’s important. Part of Family Planning NSW’s CUPID (Contraceptive Use, Pregnancy Intention and Decisions) survey found that people took the pill ‘just because’, a lot of people don’t have a reason.”

She adds that you need a lot of time to fully realise how you feel without it. She reckons a year would be enough.

I’ve been mostly free of man-made hormones for more than 10 years, but twice I’ve had to take the less-than-ideal morning after pill, and they’re full of synthetic hormones. It’s frustrating. I resent that I have to decide between knowing my body better or a safer sex life, and I hope women won’t in the future. I appreciate the work that people such as Ford do. In the past women’s fertility has been a mysterious ticking time bomb; finally it’s the topic of the hour.