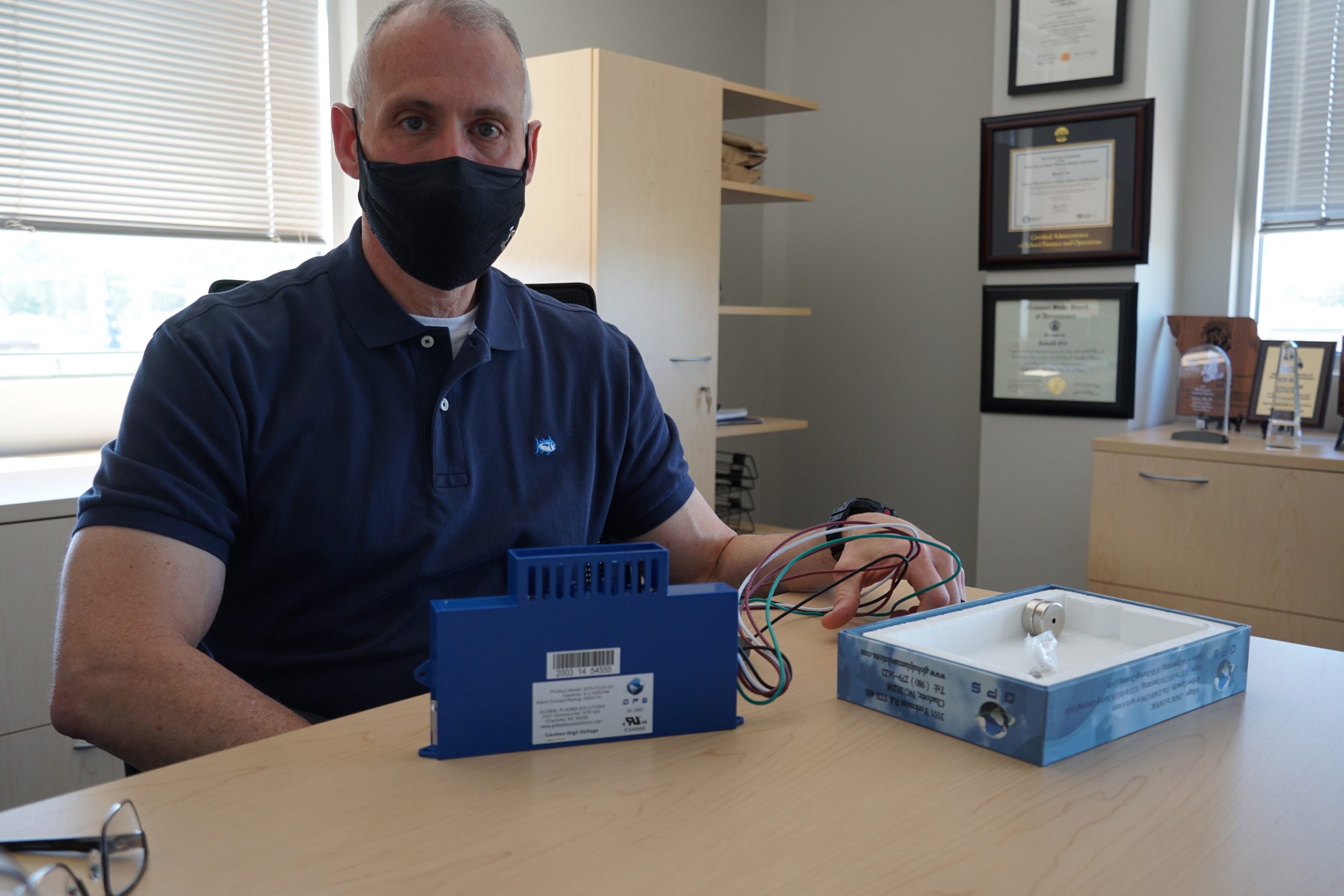

When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Scott Dulle scoured the internet for ways to safely get kids back into St. Thomas More School, a private pre-K-8 school in Kansas City, Missouri, where he works as the director of building and grounds.

When Dulle found air-purifying ionization technology that marketing materials said would inactivate over 99% of the virus that causes covid-19 in minutes, he had to have it. Parishioners who support the parochial school, some of whom were out of work, raised roughly $ 22,000 to buy the devices.

Once the units were added to the school’s air system last summer, Dulle was confident he had made the right decision.

“I knew in my heart, I knew on paper, that we were probably one of the most protected schools in Kansas City,” Dulle said.

More than 100 public and private schools in Missouri are installing air-cleaning technology to try to ease the covid fears of staff members and parents, KHN and St. Louis Public Radio found through a review of school board notes, school websites and news reports. From Dulle’s Kansas City school to the Clayton district west of St. Louis to the Jefferson City School District in central Missouri, the review found schools across the state are collectively spending over $ 3.5 million on devices that claim to reduce the covid virus.

But in April, a covid-19 commission task force for top medical journal The Lancet, composed of international health, education and air quality experts, called various air-cleaning technologies — ionization, plasma and dry hydrogen peroxide — “often unproven” with a potential to create “harmful secondary pollutants.”

School officials need to be cautious when considering installing the devices, said Yang Wang, an assistant professor in environmental engineering who studies aerosols and air quality at the Missouri University of Science and Technology. He and other air quality experts worry that some versions of the cleaners may emit byproducts such as ozone that can make people sick.

“It’s some schools influencing other schools, and they’ve heard about this thing, and they think this is quite fancy, and maybe they will make the children’s parents feel safer,” he said. “We shouldn’t easily just devote all of our resources onto this device before we know clearly what’s happening.”

At a federal regulatory level, air-purifying devices that use ionization or UV light count as devices that kill pests such as bacteria and viruses, but they do not face the same scrutiny as more traditional pesticides, said Patrick Jones, president of the Association of American Pesticide Control Officials and four lawyers who specialize in pesticide law.

Pratim Biswas, who spent years leading the Energy, Environmental and Chemical Engineering Department at Washington University in St. Louis, said not enough peer-reviewed evidence shows the devices are effective at preventing covid spread — or better than using a multilayered approach that includes low-cost solutions such as opening a window. He added that much of the testing conducted so far has occurred in laboratories, not in a classroom environment.

“People try to sell some of these devices, but there’s no shortcut,” said Biswas, now the University of Miami’s incoming dean of engineering.

Instead, Biswas, Wang and others typically recommend schools install high-quality air filters such as HEPA or more advanced MERV 13 filters, and increase the amount of outdoor air inside a room.

Even so, over 2,000 schools across 44 states have installed ion-blasting or other air-purifying technology, a KHN investigation found in May. To pay the bill, many schools have tapped into a flood of taxpayer money — roughly $ 193 billion in federal funds sent to schools to pay for anything from salaries to personal protective equipment.

In Kansas City, St. Thomas More School received about $ 11,000 in taxpayer funds to reimburse the school for half the cost of the devices it installed, Dulle said. St. Louis University High School, a private Catholic school, also used federal funds to pay for ionization technology, according to the school website and its student newspaper. St. Louis University High School did not respond to multipl

e attempts for comment.

In the St. Louis suburbs, Rockwood School District is spending more than $ 685,000 to install ionizing units across its campus. “The federal funding that has been made available absolutely was a game changer,” said Chris Freund, Rockwood’s director of facilities. “That’s really what kind of tipped the scales.”

For some larger districts, the costs add up. The public Jefferson City School District has budgeted $ 1.1 million, not from federal pandemic funding, to install ionization units in its schools, according to district spokesperson Ryan Burns. That could buy more than 3,600 Samsung Chromebook laptops for students.

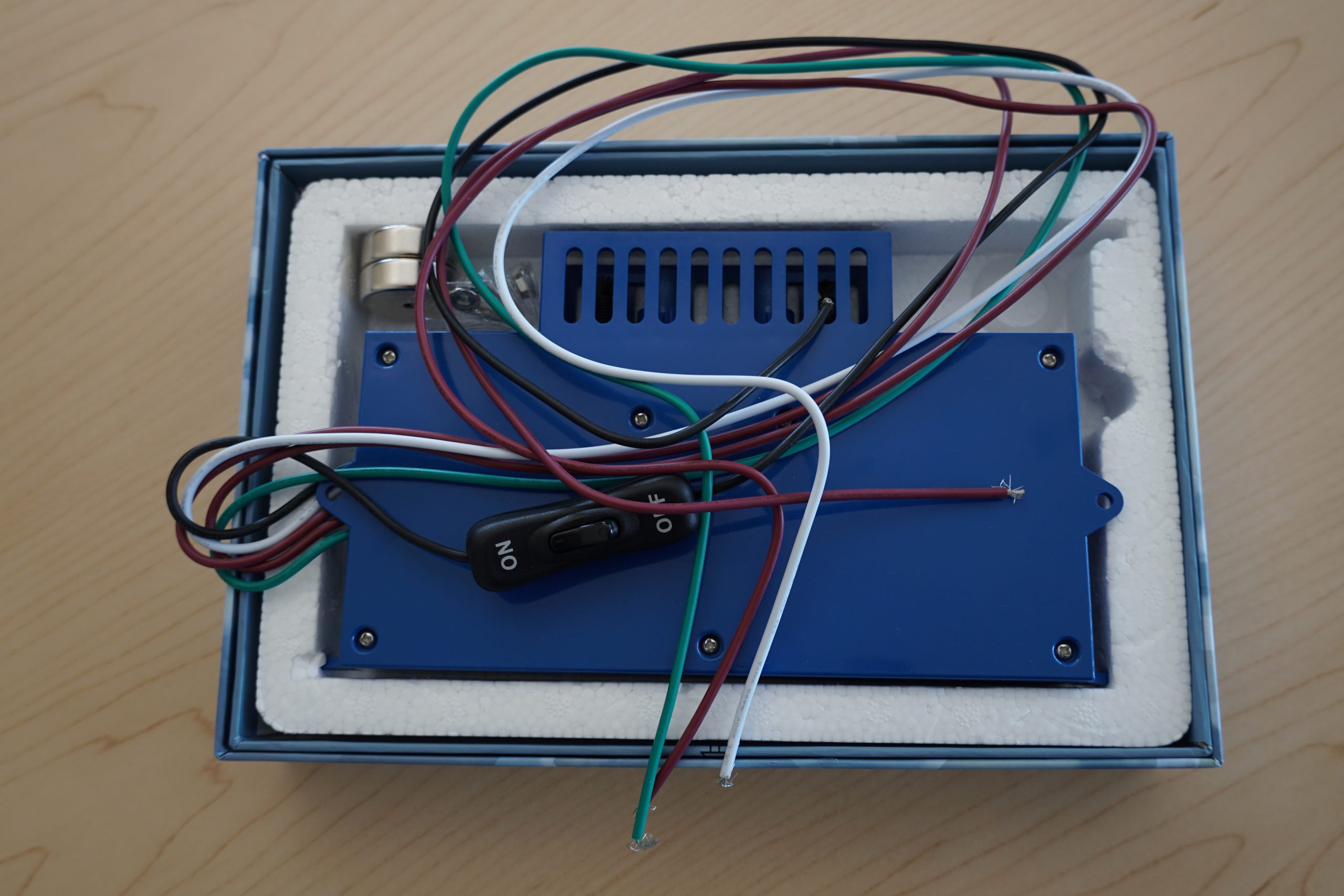

The “iWave” devices that Kansas City’s Dulle purchased rely on technology from Global Plasma Solutions. The air-purifying company’s marketing materials for its various products explain how they are designed to work: They emit charged ions into the air. Those ions “seek out” particles, like dust or pollen, and make them cluster together. Those clusters are more easily trapped inside a filter in a building’s HVAC system. The North Carolina-based company also says on its website that the ions inactivate pathogens.

The company, which has made products also being installed in Jefferson City Public Schools, St. Louis University High School and other schools in Missouri, is facing a federal lawsuit filed by a consumer who bought one of its devices, alleging the company “continues to defraud consumers by concealing material information regarding the true performance” of its products.

Company spokesperson Kevin Boyle pointed to the company’s motion to dismiss the suit. In those court documents, Global Plasma Solutions said of the lawsuit: “It is devoid of any concrete, specific allegations plausibly alleging that GPS made even a single false or deceptive statement about its products.”

Boyle said peer-reviewed research on the company’s products doesn’t exist yet for the virus that causes covid-19, but his confidence in the technology stems from the company’s testing, stories from customers and the general peer-reviewed research on the benefits of ionization.

“This technology is safe and effective,” he said, noting he was glad it was in his children’s schools. “This is not a silver bullet. This is part of a multilayered solution. And when this technology is used, it absolutely delivers incremental benefits.”

He said the ionizers from Global Plasma Solutions do not emit “harmful volumes of ozone.”

One school district in California turned off its devices when it learned of the lawsuit. Although Dulle’s Kansas City school is aware of the Global Plasma Solutions lawsuit, he said, school officials decided “we’re going to wait and see where this is going.” He said that doctors’ offices and other trusted institutions had bought the technology. And when the school bought the devices last summer, he said, school officials were “every day learning something new about the virus and how to kill it.”

In north St. Louis County, Pattonville School District has installed Global Plasma Solutions technology made possible by federal relief funds, spending over $ 330,000.

Ron Orr, chief financial officer for the district, noted the appeal of buying devices that fight more than the virus that causes covid-19, as makers of air-purifying devices often tout their ability to curb the spread of viruses that cause colds, flu and other illnesses. He is such a fan, he bought a unit to help with dirt and dander in his home — where he lives with his wife, son and three dogs.

Orr isn’t completely sold on the claims of the devices when it comes to keeping kids safe from covid: “What I will say, it makes our environment safer and healthier, because we’re filtering out more from the air than we otherwise would be.”

He said the price also was hard to beat compared with replacing the district’s entire HVAC systems with a higher filtration option.

“Is there any way that we can get to that standard, without having to replace $ 40 million in heating and cooling equipment, which just physically wasn’t something that was going to be possible?” Orr asked. “And so that’s what kind of led us down this road.”