A group of nurses take their spots on a sidewalk in late April a little before sunset. They’re holding candles. When 136 people from around the world have joined the vigil by video conference, they light their flames for Celia and touch them to a wick.

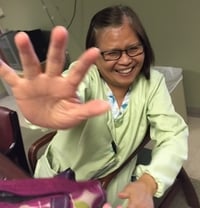

Two days earlier, Celia Yap-Banago died alone in her bedroom weeks after caring for a patient suspected of having covid-19 at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, Mo. Celia wasn’t just a registered nurse who would have celebrated 40 years in the profession that month. At 69, she was the plain-spoken, slightly inappropriate, kind-of-nosy mother figure of 4 North, the cardiac telemetry unit that had become an overflow ward for patients with covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

“I just wish …” Jenn Caldwell, a nurse at Research who spent years working alongside Celia, says after the vigil starts. “I wish things would’ve went a lot differently.”

But instead Celia is gone, one of hundreds of U.S. health-care workers — not just nurses and physicians but also EMTs, paramedics and medical technologists — who’ve died fighting a virus against which humans have no known immunity. There is no official tally of their deaths. More than 77,800 have tested positive for the coronavirus, and more than 400 have died, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which acknowledges that’s a significant undercount. The nation’s largest nurses union, National Nurses United, puts the total much higher: 939 fatalities among health-care workers, based on reports from its chapters around the country, social media and obituaries. Nurses represent about 15 percent of those deaths, the union said.

Celia Yap-Banago and her husband, Amado, had planned to travel to their native Philippines next year to renew their vows to celebrate 35 years of marriage. “We had it all planned out,” their son Jhulan said. (Jhulan Banago)

And those may be just the first casualties, with new coronavirus cases surging in parts of the South and the Far West and the possibility of a second wave of the pandemic in the fall.

Co-workers of those who’ve died have been left to deal not just with grief but a mix of anger, frustration and fear. Heath care, after all, is as much a calling as a job for many of them; during a pandemic, learning a colleague or relative is infected or worse means an almost daily reckoning — not just with one’s own mortality, but also with a growing sense of powerlessness.

“This has been bigger than anything I ever imagined,” said Lilian Abbo, an infectious-disease specialist in Miami who in January began advising Jackson Health System on how to prepare for the virus. “We worked so hard for so many months. But we are not gods.”

Simply reporting for work can mean gambling with your life, and the odds grow longer when masks and other personal protective equipment become difficult to get. Nurses United sent a letter to hospitals in late January urging increases in PPE inventory, such as N95 respirators and eye coverings.

“We recommend the hospital should prepare now,” the union wrote Jan. 24 to HCA Midwest Health, an arm of the nationwide conglomerate that manages Research Medical Center.

Four months later, a nationwide PPE shortage has emerged as one of the pandemic’s most incendiary side effects. Health-care workers have staged protests to honor fallen colleagues and also to demand that their employers — and President Trump — make additional equipment available. Some hospitals have disciplined workers who flouted policies meant to conserve equipment: A Chicago nurse with asthma said in a lawsuit that she was fired after warning co-workers that she felt the masks provided by her hospital were not adequate; in California, 10 nurses were suspended after demanding protective gear (and then reinstated after union intervention).

In Kansas City, some of Celia’s colleagues and family members believe her death could be traced to Research’s decision to carefully control access to PPE and, some nurses say, discourage staff from requesting it. Protective masks and other equipment were removed from nursing stations and stored in a conference room on the first floor, according to interviews with hospital staff.

HCA Midwest spokeswoman Christine Hamele said the system followed CDC guidelines to conserve equipment as it faced an uncertain future.

“We knew that our need for PPE far outweighed the supply and we could not predict how long the pandemic would last or how long it would take to source new supplies,” Hamele wrote in an email statement to The Washington Post. “A centralized location and process for PPE is industry best practice.”

Workers said that when they needed items, they had to provide their full name and identification number, alongside the request. As the virus spread and workers’ shifts became chaotic, some just didn’t bother.

“We get such a pushback that sometimes you don’t feel like it’s worth saying anything, because nobody listens and nobody cares,” said Charlene Carter, a night-shift nurse at Research. “You want to stand up for what you know is right, but you know you’re going to get reprimanded somehow.”

Research Medical Center nurse Charlene Carter warned colleague Yap-Banago to be careful with a patient she suspect of having covid-19. All three would have the disease; only Carter survived. (Christopher Smith for The Washington Post)

On March 22, Carter’s patients included a woman she suspected of having covid-19. Before going home that morning, she told the nurse who’d relieve her to be careful and wear protective equipment. A few days later, both Carter and Celia would test positive for the coronavirus. Carter, 36, recovered. The patient and Celia did not.

Now Carter is with her colleagues on this dimly lit sidewalk, and soon this vigil starts taking on the feeling of a protest. Caldwell looks into a camera and vows that Celia’s death will not be in vain. Carter challenges other nurses to fight for what they need.

Click any underlined name to view their obituary in a new tab.

Another nurse, Leo Fuller, steps forward and solemnly reads from a list of fallen health-care workers from around the United States: Jeff Baumbach, 57, from California; Aleyamma John, 65, from New York; Araceli Ilagan, 63, from Miami. No one can say how many of those people died because of insufficient PPE, inadequate testing or other issues. What is undeniable is that all of them put their lives at risk to care for others because that’s what they do. Some also lived and worked in communities with widespread transmission. Still, a series of “what ifs” haunt some of their friends, relatives and colleagues.

Fuller flips the page. She left Research last October, begging Celia to come with her so they could travel the world. But Celia kept working, undeterred by age or even a deadly virus, and now she had one more thing in common with the names Fuller is reading: Daisy Doronila, 60, from New Jersey; Kious Kelly, 48, from New York City; Freda Ocran, 50, from the Bronx.

Fuller again turns the page and keeps reading. With 54 names to announce, she turns it again.

Before she died, Celia had plans, like so many health-care workers whose lives ended because they’d fought a deadly virus. A year from now, she and her husband, Amado, would travel to their native Philippines to celebrate 35 years of marriage and renew their vows. Josh, their younger son, would be Amado’s best man; Jhulan, their 28-year-old, would walk his mom down the aisle.

“We had it all planned out,” Jhulan says.

In South Florida, 67-year-old internist Alex Hsu was excited about spending time with his grandchildren. In the Bronx, 59-year-old surgeon Ronald Verrier had been thinking about a family reunion in Atlanta, where his daughter had recently bought a house. In New Jersey, 24-year-old paramedic Kevin Leiva and his wife were dreaming big: eliminating their debts, buying a little farm in Maine, having a couple of kids.

Lisa Ewald told friends she was not provided with a mask even when assigned to a patient suspected of having covid-19. She died of the disease in March. (Roger Chow)

In Detroit, 53-year-old nurse Lisa Ewald was just looking forward to tomorrow morning, because that’s when Roger Chow sent his daily texts.

“Morning Lisa,” he sent one day in March.

“Morning Roger!” Lisa replied.

They called each other friends, though people who knew them wondered if they were something more. They’d met in 2004 during a Star Trek cruise, went on vacations together, ended conversations with “love you” and heart emoji. She was planning an April trip to Rockville, Md., where Roger works in information technology, and for her birthday, Lisa wanted to see the cherry blossoms along the Tidal Basin. If one of them didn’t respond to a text, the other worried something was wrong.

Roger had grown increasingly concerned about the coronavirus, and he told Lisa a co-worker had tested positive. She told him when she treated covid-19 patients at Henry Ford Health System, where she worked; she also confided to him when one of those patients died, and when she was asked to reuse protective equipment. Lisa told friends she hadn’t been provided a mask even when assigned a patient with a suspected case, and by early April, more than 700 of the system’s employees had tested positive, hospital officials said in a statement then.

“I’m sure I will get it,” Lisa texted Roger on March 21, and the next day she predicted the outbreak in Michigan would be severe.

Roger Chow mourns the loss of Ewald, a nurse at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit. (Amanda Voisard/for The Washington Post)

She was, in fact, correct on both accounts. By late March, the state’s confirmed cases were doubling every three days, and Lisa told Roger on a Tuesday that she had been exposed — but that the hospital wouldn’t test her unless she showed symptoms. They joked that you had to be a politician or a professional athlete to get tested.

“Morning Lisa,” Roger texted one morning.

“Morning … I really don’t feel well,” Lisa replied.

The hours passed, and Lisa took a survey that advised her to contact employee health services at Henry Ford. Her calls went straight to voice mail and initially went unreturned. Lisa was turned away from the emergency room though she had a fever of 103 degrees; a drive-through clinic the ER had referred her to was closed. Her skin became sensitive to the touch, and chills and body aches made it impossible to sleep. She curled up with Max, her cat, and apologized to Roger for complaining about her symptoms and frustrations.

“You can say whatever u want to me,” he texted, though he’d wonder later if he should’ve said more to Lisa — including u

rging her to go back to the hospital.

Nearly a week after her presumed exposure, Lisa texted Roger a picture of her positive test for the coronavirus. She was still waiting for a doctor from employee health to call, hopeful she’d be prescribed medication. She said she felt alone. A couple who lived next door left medicine and food on her doorstep, but knowing all too well how swiftly the virus spread, Lisa refused to crack the door until they were out of sight.

Chow holds a photo from a 2018 vacation he took with Ewald to Universal Orlando Resort. (Amanda Voisard/for The Washington Post)

In a statement, a Henry Ford Health System spokeswoman cited privacy concerns in refusing to answer questions about why an employee was not immediately tested and later turned away from the hospital. The statement didn’t address Lisa’s access to PPE but said the system prioritized testing employees and providing masks, gowns and other protective equipment. “Fresh supplies” were maintained for team members, the spokeswoman said.

The days crawled by, and if Lisa looked forward to mornings, she now dreaded evenings. That’s when the fever spiked and her symptoms intensified. She tried to get comfortable, to be hopeful.

On the final Monday of March, a few hours after learning she’d indeed contracted covid-19, Lisa sat on her sofa and watched television. Around 7:30 p.m., she told Roger she felt terrible.

Twelve hours later, he texted as always.

“Morning Lisa,” he wrote.

She didn’t respond. Neighbors would later find her still upright on the couch, the TV still on. But that day, as the hours passed, Roger kept hoping. He called. No answer.

And in the afternoon, he texted again.

“Hey,” he wrote. “U there …”

For most of her career, Carter, Celia’s co-worker in Kansas City, has felt an almost intoxicating joy when a patient’s condition improved. Someone had been assigned to her on what might have been the worst day of their life, and Carter could make it better.

“I made a difference,” she’d say, and though the shifts could be exhausting and the years could be a blur, the rewards of nursing made it more than a profession. “That’s big. I can’t think of too many things that’s bigger.”

Shifts flew by not just because of a cascade of responsibilities but also because her unit was filled with characters and gossip. Almost no one trafficked information like Celia. She quizzed her single colleagues on whom they were dating, insisted on being a bridesmaid if a co-worker was planning a wedding, never had a problem telling an overbearing charge nurse to shove it.

That was Celia, but after four decades in hospitals, the job was also a big part of who she was — an unmistakably common feeling in this line of work. When Verrier, the Bronx surgeon, had a heart attack six years ago, seemingly all he talked about was getting back to work. Paul Novicki, 51, loved being a paramedic near Detroit so much that when his shifts ended, he usually fired up television shows about first responders; even when Novicki retired from his local fire department, he went to work for a private ambulance company. In Brooklyn, 61-year-old physician assistant Madhvi Aya had been a doctor in her native India, and even decades after she lost her father to a heart attack, Aya believed she had the power to spare other families such pain.

In Kansas City, Celia had entered nursing because her family had worked in health care in the Philippines. She stayed in the job because it offered fulfillment, purpose, excitement. Being at home was boring, she’d tell her colleagues. Travel could be stressful. And if someone joked with Celia about retiring, she always answered the same way: They’ll have to drag me out.

By early March, Celia and her colleagues knew the coronavirus was coming as hospitals raced to be ready. Employees at Research murmured with frustration when new policies were announced “every three or four hours,” an emergency room nurse says. Disease experts warned of a dramatic need for additional staffing, more ventilators and increasingly scarce equipment, such as N95 masks that can filter out most airborne particles.

Caldwell, a longtime RN at Research and the hospital’s union representative, was temporarily transferred to 4 North in March when covid-19 cases overflowed, spilling into other wards. On her first day, Caldwell says, she was issued a disposable gown but told not to throw it away; she was to wipe down the gown, goggles and mask if she treated a suspected covid-19 patient. If a patient’s status wasn’t confirmed, nurses were encouraged to carry their masks in a paper bag so particles that became attached to the mask would be contained between uses. Shoe coverings were not issued, Caldwell says, and equipment was to be returned to the conference room at the end of each shift so it could be sterilized and reused.

“Like lambs to the slaughter,” she says. “At the end of the day, that’s how it feels. I’m not a soldier, I’m not a hero, I didn’t sign up to lay my life down. But if we continue to not have what we need, then that’s essentially what ends up happening.”

Hamele, the HCA Midwest spokeswoman, acknowledged that items were collected and stored at Research but adamantly denied equipment was reused. In an interview arranged by the hospital system, emergency room nurse Andy McClure said he has never felt unsafe at work as a result of insufficient PPE.

“I know our leaders are doing everything possible to protect us so we can be the best nurse, and be there for our patients,” said McClure, who because he is in management is not a member of a nurses union. “We kind of get what we need. I’ve never had any pushback or anything for asking for another 10, 15, 20 N95s. I never have.”

Carter, though, says she didn’t feel comfortable requesting certain equipment unless a patient was confirmed as having covid-19 and felt intimidated to “make a huge deal about it” to her superiors. On that Sunday in March, Carter says, she wore no mask while caring for the patient being examined for the virus. When her shift end

ed and Celia prepared to head in, Carter says she warned her co-worker what she could be walking into.

Weeks later, Carter would be left feeling overwhelming guilt.

“I said something,” she’ll say. “But maybe I should’ve said something more.”

She pauses, beating back tears.

“Maybe I should’ve never walked in that room,” she says. “Maybe I should’ve made such a big fit that they had to listen to me.”

Four months ago in Miami, Abbo, the infectious-disease specialist, monitored the growing crisis in Asia along with forecasts for the United States. She began working on a blueprint to respond to the pathogen. Jackson Health, one of the nation’s largest hospital systems, wouldn’t just need to load up on PPE, which a system spokeswoman said it did by nearly quadrupling N95 respirators between January and March and more than doubling its inventory of shoe coverings and coveralls. Employees would need extensive training on not just wearing unfamiliar equipment but how to treat the sick and comfort the dying.

“We don’t have to be like New York,” Abbo would remember thinking as the weeks passed, the virus arrived and spread, and many hospitals there became overwhelmed.

But as cases surged in the nation’s largest city, health-care workers there routinely subverted instructions and followed their instincts. Often staffers in New York hospitals erred on the side of compassion — even if it put them at increased risk. One nurse described how they had been instructed not to perform certain procedures without full protective equipment because of the risk of aerosolizing the virus and infecting staff. But when she was confronted with a patient who was talking one minute and then stopped breathing in front of the emergency department doors, she said she had no time to put on additional gear. So she broke protocol and started chest compressions.

EMTs, ordered not to enter homes without head-to-toe protective gear, found themselves rushing in wearing partial equipment because if a patient’s heart stopped, seconds could separate life from death. One nurse would recount how a covid-19 patient’s ventilator tube came loose, and without immediate action, the patient would die. With the nearest N95 masks across a hallway, the nurse held his breath, ran in and reconnected the tube. In the days before the death of Kious Kelly, an RN at Mount Sinai West hospital in Manhattan, nurses posted photos of themselves on social media wrapped in trash bags because of scarce PPE. Mount Sinai has disputed that supplies were inadequate, saying the hospital system always provides “all our staff with the critically important PPE they need to safely do their job.”

Abbo hoped to avoid such catastrophe. But in late March, her phone rang. Her great-uncle and great-aunt were sick, their conditions deteriorating, in need of intensive care. “A stab in the heart,” Abbo would say, and she made the 13-mile drive to the hospital in nine minutes before admitting the elderly couple two beds apart.

Besides being a relative, Isaac Abadi had been Abbo’s most exacting professor when she attended medical school in their native Venezuela. Now 84, he was still seeing rheumatology patients there before a visit to Miami in early March. When Abbo reached his bedside, Abadi maintained a clinical fascination with the virus now killing him. He researched anti-inflammatory medications and asked his niece to text him results from his own X-rays and bloodwork. Though it was unorthodox, Abbo obliged.

Isaac Abadi, who died from covid-19. (Family photo)

The days passed, and as Aunt Aviva showed improvement and would be discharged, Uncle Isaac kept getting worse. Among the protocols Abbo had helped implement was a strict no-visitors policy in the hospitals’ covid-19 wards. But this was her uncle, so she pulled on full protective equipment and brought food into Abadi’s room. She fed him, talked to him, held his hand.

“I was willing to do things that nurses may not be willing to do,” Abbo says now.

She prayed with her uncle and allowed him to determine his treatment plan: no dialysis, no intubation, no resuscitation. She stopped in several times a day to check on him. Abbo was afraid that if she went home, her uncle would die alone, as so many others had.

“My husband, my parents, my children are asking: ‘Why are you going and exposing yourself?’ ” she says. “I have to do what I have to do.”

When the end came for Abadi, he indeed was not alone. Abbo gave her aunt a mask and brought her to a doorway to say goodbye. Then Aunt Aviva left, and Uncle Isaac’s niece held his hand as he drew his last breath.

When it was over, Abbo went back to work. Her mission remained, though it was now tethered to a growing sense of futility.

“This is someone that I loved nearly and dearly,” she says, “and not being able to save his life …”

She trails off.

“Everyone is saying, you’re Wonder Woman, and calling you a superhero,” she says. “And I’m like: ‘No. I’m not.’ ”

A little more than a month ago, Charlene Carter waited in the Research Medical Center parking garage and could feel her heart racing. It was her first day back at work since contracting covid-19.

What would happen if she walked inside and started her shift? Could she be reinfected? Would she have access to the masks and other equipment? Would she feel safe?

“Things are going to be better,” she’d remember telling herself.

This was 11 days before Celia died of the same virus Carter had somehow beaten, though her chest still hurt and she worried about permanent lung damage. Considering she had always identified as a nurse, Carter now felt as if her employer hadn’t just failed her. She felt betrayed. Some of her co-workers told her they remained frustrated. While Research had added protective equipment, some said N95 masks and portable air purifiers were still scarce. Since Carter had been out sick, staffers now entered and left through a single set of automatic doors, the hospital restricted visitors, and wo

rkers took employees’ temperature before issuing a surgical mask.

“This is what you do,” nurse Charlene Carter recalled telling herself as she summoned the fortitude to return to work after recovering from covid-19. (Christopher Smith for The Washington Post)

After Celia’s death, registered nurse Caldwell would say a shift now meant wrestling with an impossible choice: Stay home and guarantee her own safety, or continue the fight of her life — even if it could kill her?

“A little bit of a struggle to go back every day,” she’d say.

In early May, Celia’s family held a small funeral — 10 visitors went in as another 10 came out — and the hospital celebrated her 40th anniversary by announcing a nursing scholarship in her name and presenting her family with her stethoscope. Her husband and sons carried on talking about her in the present tense, filling a plate for her at dinner, leaving her television on the Hallmark Channel each night because that’s how she liked to fall asleep.

Then, a few weeks later, they filed a workers’ compensation claim against the hospital, alleging Celia had requested PPE but had been denied. (In a statement, HCA Midwest Health credited Celia’s impact as a nurse and mentor, and said officials hoped for a “swift resolution” to the legal proceedings.) Sometimes her son Jhulan wonders if, as the virus closed in, he should have insisted his mother retire, or just take time off. But Celia was Celia, and he knows what her response would’ve been.

“It was her calling,” he says. “She knew the risks and still wanted to help.”

On that evening in early April, Carter sat in her Dodge and tried to stave off a panic attack. She thought of her 11-year-old daughter and briefly considered restarting the car and heading home. But she didn’t, because another thought entered her mind.

“This is what you do,” Carter would recall telling herself, and she opened her door and passed through the garage.

Her heart still pounding, her mind still wandering, she imagined what the following hours and days would be like. She wondered how 4 North would feel now; if this experience had changed her. But then she stepped forward, the automatic doors opened, and Carter took a breath and walked in.