Department of Health WITHDRAWS official UK Coronavirus daily death toll of 114 after it emerges nobody in England is ever counted as cured

- Department of Health figures show 82 Britons are now succumbing to the life-threatening infection each day

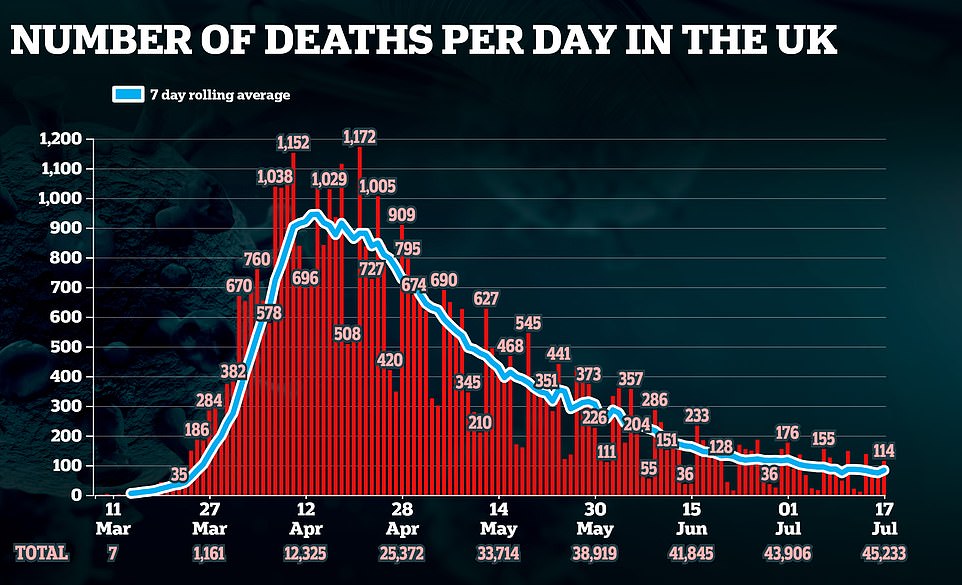

- The seven-day average was 74 last Friday. More than 1,000 people died each day during the peak in April

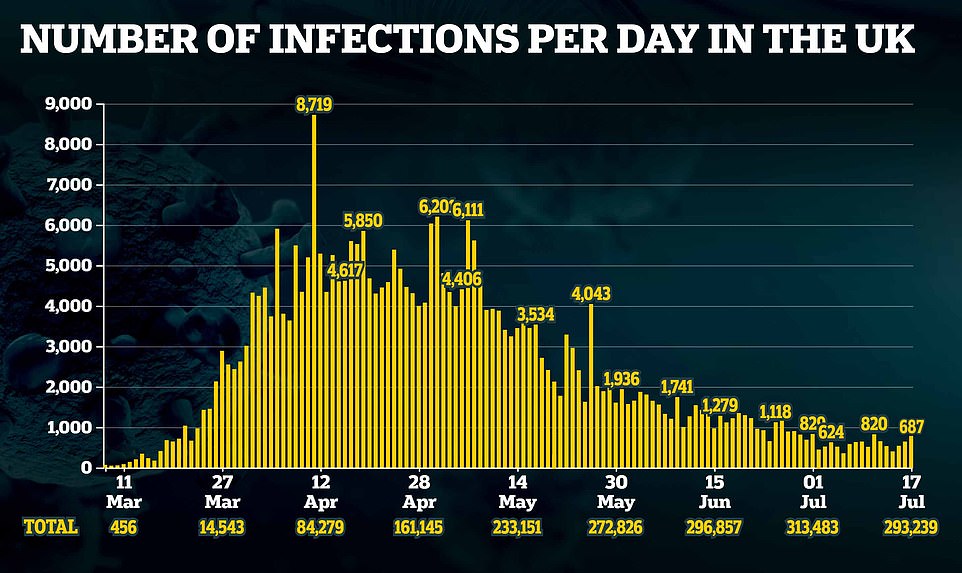

- Data also revealed a similar jump in cases, with officials today confirming 687 more Brits had tested positive

- It means 609 new cases are being diagnosed each day on average – up from the mean of 556 last Friday

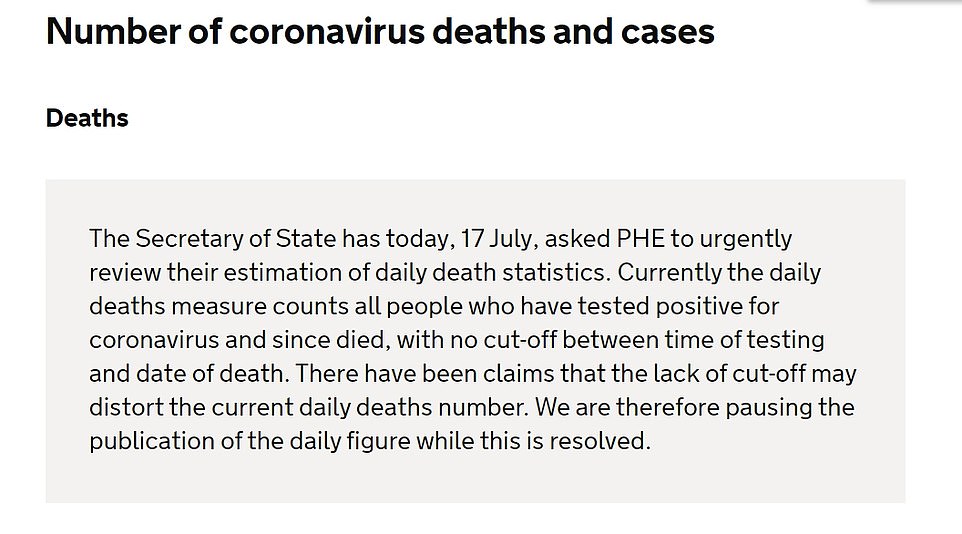

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has ‘paused’ publication of the daily coronavirus death figures as Matt Hancock orders an urgent review into how the numbers are calculated.

Another 114 UK victims were announced on Friday, but researchers criticised ‘statistical flaws’ in the way the deaths are reported across England, saying they are left looking far worse than any other part of the country.

Public Health England’s figures figures feed into the daily death statistics published by the DHSC, with information from Public Health Wales, Health Protection Scotland and the Northern Ireland Public Health Agency also fed in.

According to a note on the Government’s website, the review means it is ‘pausing’ the publication of the daily death figure ‘while this is resolved’.

The daily DHSC data represents the number of reported deaths of people who have tested positive for Covid-19, who have died in all settings.

But in a blog entitled ‘Why no-one can ever recover from Covid-19 in England – a statistical anomaly’, Professors Yoon Loke, from the University of East Anglia, and Carl Heneghan, from the University of Oxford, said more robust data is needed.

They argued that PHE looks at whether a person has ever tested positive and whether they are still alive at a later date.

This means anyone who has ever tested positive for Covid-19 and then dies is included in the death figures, even if they have died from something else.

DHSC’s announcement sparked frustration and disbelief on social media, however, with one user writing: ‘I suggest you get someone to pull their finger out and get this sorted over the weekend. Behave like a private sector company would when its reputation has tanked.’

Another added: ‘Still not able to count the number of people being tested each day I see. I must admit that is a tricky thing to do.’

A third said: ‘Can this be resolved ASAP so we have daily figures to gauge the danger we are in. Please do not let this drag.’

Health Secretary Matt Hancock, pictured in the Commons on Thursday, has ordered an urgent review into how the numbers are calculated

The announcement posted on the Department for Health and Social Care website regarding daily death statistics

The department’s announcement on Friday evening sparked frustration and disbelief from many on social media

Earlier today, 114 more coronavirus victims were recorded, with the rolling average number of deaths now 10 per cent higher than last week amid accusations the government’s official daily counts are too high.

Department of Health figures show 82 Britons are now succumbing to the life-threatening infection each day – up from the seven-day mean of 74 last Friday. More than 1,000 people were dying each day during the darkest days of the crisis in April.

Alarming statistics also reveal a similar jump in cases. Officials today confirmed 687 more Brits had tested positive for Covid-19 – the equivalent of 609 each day over the past week. For comparison, the rate last Friday was 556.

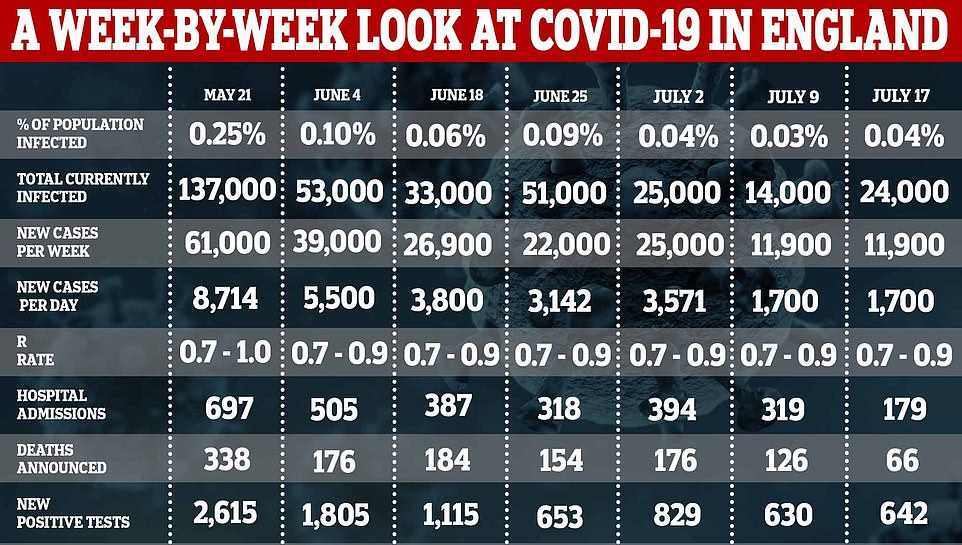

Other troublesome data released today, by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), warned 1,700 people are still catching the illness every day in England – exactly the same estimate as last week.

But while an array of data suggests the outbreak is inevitably getting worse after Boris Johnson relaxed lockdown rules to allow millions of Britons to enjoy some summer freedom, scientists today claimed there is ‘no indication’ the crisis has ‘gotten out of hand’ as a result of the easing of the draconian measures.

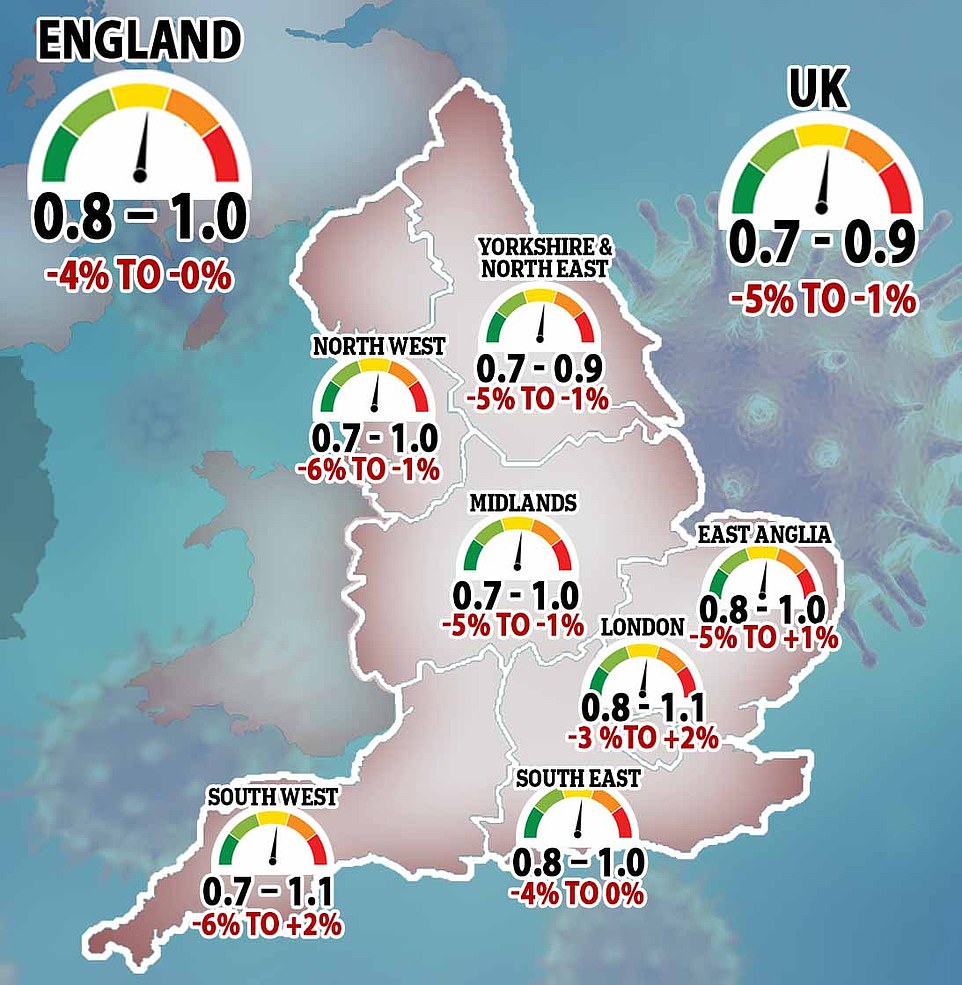

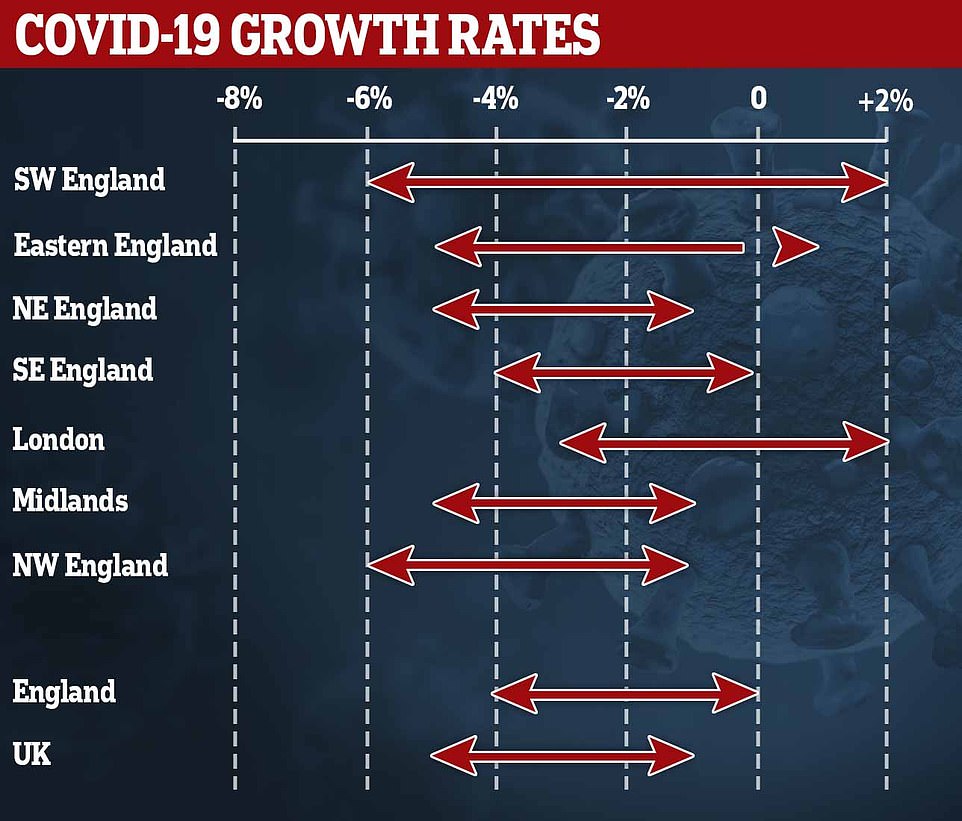

Their comments came after Number 10’s scientific advisers today revealed Britain’s coronavirus outbreak is still shrinking by up to 5 per cent each day. But SAGE also warned the R rate could be above one in the South West of England and London and is only definitely below the dreaded number in the North East and Yorkshire.

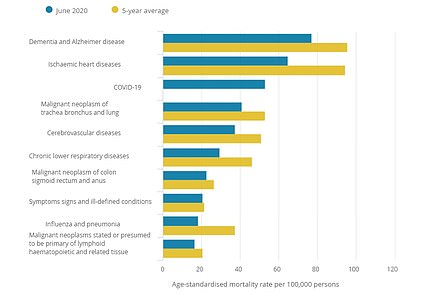

Separate ONS figures today also revealed coronavirus is no longer the leading cause of death in England and Wales. But the same official figures showed it was still the third most common way to die in June, behind only dementia and heart disease.

The catalogue of figures come after Health Secretary Matt Hancock today ordered Public Health England to review the way it counts deaths because of a ‘statistical flaw’ that means officials are ‘over-exaggerating’ the daily toll.

PHE counts people as victims if they die of any cause any time after testing positive for Covid-19 – even if they were hit by a bus months after beating the life-threatening infection, top academics revealed last night. The method is likely why the daily fatality tolls are not dropping quickly in England because survivors never truly recover from the disease as their deaths are blamed on the coronavirus – regardless of their real cause.

And the data came as the UK’s chief scientist Sir Patrick Vallance today warned that Britain could need another national lockdown this winter just hours after Boris Johnson announced plans to try and get the country back to normal by Christmas.

Boris Johnson today urged all workers to return to offices in August as he set out his timetable for life in the UK to return to normal this winter. In a Downing Street press conference, he revealed restrictions on the use of public transport in England are being dropped immediately with trips on the train and bus to no longer be viewed as the option of last resort. But scientists and medics fear the move out of lockdown is too ‘rash’ and could risk a second wave this winter.

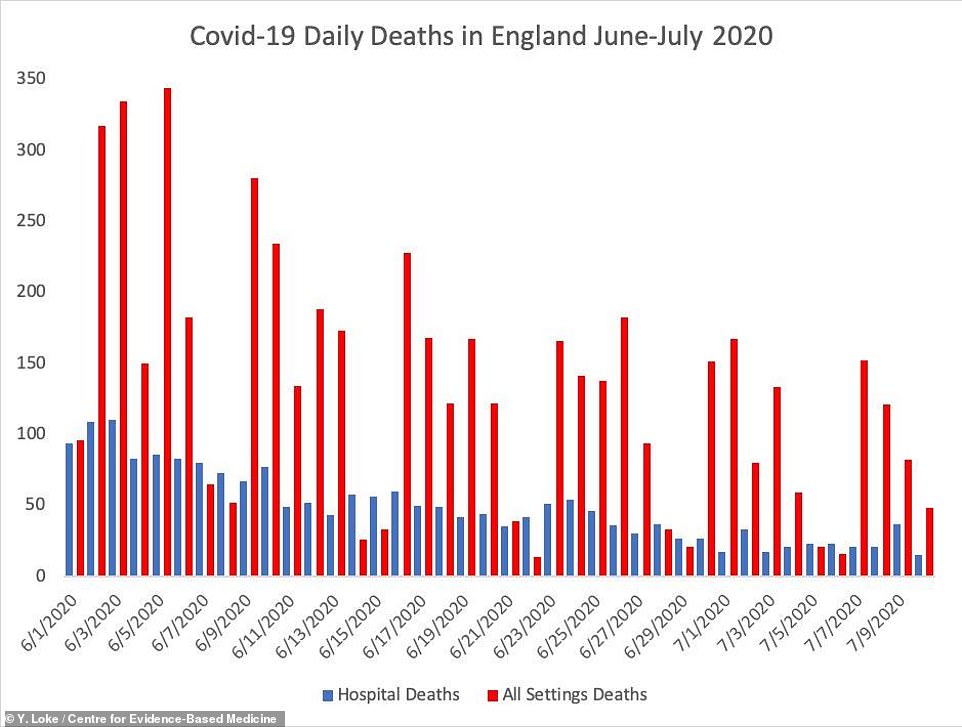

Dr Loke’s analysis shows that ‘all settings’ deaths (red bar) remain very high in England even as hospital deaths (blue bar) – which the Office for National Statistics says should make up two thirds of the total – have plummeted

In other coronavirus developments in Britain today:

- Security Minister James Brokenshire said the UK is at least ’95 per cent’ certain the Kremlin gave the green light for Russian cyber attacks designed to steal coronavirus vaccine research;

- Britain could already have herd immunity against Covid-19 because so many people have had similar illnesses in the past, an Oxford University study claimed;

- Half a million coronavirus tests made by Randox and used by thousands of Britons were recalled after spot checks revealed they were not sterile.

And the count announced by NHS England every afternoon — which only takes into account deaths in hospitals — does not match up with the DH figures because they work off a different recording system.

For instance, some deaths announced by NHS England bosses will have already been counted by the Department of Health, which records fatalities ‘as soon as they are available’.

More than 1,000 infected Brits died each day during the darkest days of the crisis in mid-April but the number of victims had been dropping by around 20 to 30 per cent week-on-week since the start of May.

NHS England today posted 16 deaths in hospitals across the country, including none in London for the second day in a row or the South West. One fatality was recorded in all settings in Wales but none were registered in either Scotland or Northern Ireland, according to official updates.

It comes as two leading experts who uncovered the flaw in the way PHE counts deaths today told MailOnline their ‘best guess’ was that more than 1,000 people have had their deaths wrongly recorded as caused by Covid-19.

Dr Yoon Loke, a pharmacologist at the University of East Anglia, warned that it is ‘not a good way of collecting data’, has had a significant impact in the past two months and is happening because PHE ‘chose a quick and easy technique’.

And the daily death tolls may not hit zero ‘for months to come’ because of a long tail of elderly people who beat Covid-19 but will die of other causes, Dr Loke added. He uncovered the flaw alongside Oxford University’s Professor Carl Heneghan.

Dr Loke said: ‘By this PHE definition, no-one with Covid in England is allowed to ever recover from their illness.’

Prime Minister Boris Johnson confirmed in a press conference today that the Health Secretary has ordered PHE to review the way it is counting people’s deaths.

It comes after a string of mistakes at PHE, including stopping testing and tracing at the peak of Britain’s outbreak. Tory MP David Davis this month told MailOnline the organisation had ‘made a complete mess’ of Covid-19 testing.

A Department of Health spokesperson said today: ‘The Health Secretary has asked Public Health England to conduct an urgent review into the reporting of deaths statistics, aimed at providing greater clarity on the number of fatalities related to Covid-19 as we move past the peak of the virus.’

The way PHE counts victims on a daily basis works by it combing through records of people who have tested positive for Covid-19 in the past to see if they have died. If they have, their death is automatically added to the coronavirus count.

It means that if, for example, somebody tested positive in April but recovered and was then hit by a bus in July, they would still be counted as a Covid-19 victim.

Dr Loke pointed out that unless PHE changes its system, all 292,000 people who have tested positive so far will be added to the Covid-19 death toll when they eventually die.

The Department of Health, which uses PHE’s data for its daily announcements, has so far counted 45,119 fatalities with 66 announced yesterday.

The ‘statistical flaw’ should not drastically affect the total number of deaths but means the ongoing death tolls appear worse than the reality.

The Office for National Statistics – which is not affected by the counting method – has confirmed at least 50,698 people have died in England and Wales up to July 3.

Public Health England admitted it is counting the deaths of anyone who tests positive for Covid-19, regardless of how long afterwards they died.

Dr Loke said: ‘It seems that PHE regularly looks for people on the NHS database who have ever tested positive, and simply checks to see if they are still alive or not.

‘PHE does not appear to consider how long ago the Covid-19 test result was, nor whether the person has been successfully treated in hospital and discharged to the community.

‘Anyone who has tested Covid-19 positive but subsequently died at a later date of any cause will be included on the PHE Covid-19 death figures… even if they had a heart attack or were run over by a bus three months later.’

The pharmacologist, who published his findings in a blog post last night, said the bizarre way of recording deaths is why there are such wide variations in daily figures.

On Monday July 6, for example, 16 deaths were recorded, while 152 were announced the next day on Tuesday the 7th.

The Department of Health has blamed low numbers on Sundays and Mondays on a ‘weekend effect’ which means paperwork doesn’t get completed.

But academics are increasingly confused about why there are such wild variations, and why the number of deaths seems to remain so high.

And it appears to be simply that anyone who dies after being added to a register of people who have tested positive is classified as a victim.

It is currently impossible to know how many of the deaths announced by the Department of Health were not actually caused directly by Covid-19.

Dr Loke told MailOnline: ‘This is a very serious issue for public confidence.

‘When you go onto social media you will see hundreds of posts from rightly anxious people who are petrified at the seemingly relentless, unyielding daily death toll in England. The public are scared.

‘The public are asking questions about why England is doing so badly, when actually the truth is that the healthcare professionals in NHS are doing a great job in ensuring thousands of Covid survivors. The statistics here are misleading the public.

‘Because of this major flaw in the statistics, and the fact that tens of thousands of older people are being monitored, there is going to be a very very long tail of daily deaths.

‘The death toll will go down exceedingly slowly. It’s certainly not going to get to zero for months to come yet, because older people who have recovered from Covid-19 will unfortunately still succumb to other illnesses.’

Professor Carl Heneghan and Dr Jason Oke, Oxford University researchers who published Dr Loke’s work on their website, said that officials also seem to be spreading out historical deaths and just adding them on to ones that are happening now.

The pair pointed out the death counts from NHS England, which are accurate around three days after the date in question, are too low to match counts from PHE.

According to the Office for National Statistics, hospital fatalities now make up around 60 per cent of all deaths that happen on any given day.

On June 30, NHS England recorded 27 fatalities. If this was 60 per cent of all deaths that happened on that day the total number would be 45.

But the Department of Health, using PHE’s data, announced 115 more deaths on that day.

Dr Loke now suggests these massively inflated numbers are because PHE is counting people who died outside of hospital but didn’t die of coronavirus at all.

He wrote: ‘PHE data confirm that more than 125,000 patients have been admitted to NHS hospitals for Covid-19, the majority being successfully treated and discharged.

‘There are now less than 1,900 patients in hospital. So, roughly 80,000 recovered patients in the community will continue being monitored by PHE for the daily death statistics.

‘More and more people (who are mainly in the older age group) are being discharged to the community, but they clearly may die of other illnesses.’

Dr Loke said it would be a ‘reasonable approach’ to set a three-week limit on blaming someone’s death on coronavirus unless they were in hospital.

Public Health England told MailOnline that the World Health Organization has not defined a time limit for counting a death as caused by Covid-19, and said it ‘continues to keep this under review’.

It admitted that a coronavirus death is a death that happens to anyone who has previously tested positive, regardless of how long ago the test happened.

It said the ‘vast majority’ of Covid-19 deaths are correctly identified.

Dr Loke added: ‘This statistical flaw arose because PHE chose a quick and easy technique.

‘Their statistical method is reasonably accurate at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were not yet many people in the community who had survived Covid.

‘However, PHE did not – and have not yet – realised that glaring inaccuracies arise when tens of thousands of frail older people are discharged from hospital, and these Covid survivors unfortunately die from other, non-Covid related causes.

‘Like most things that are a quick fix, the monitoring system eventually churns out gibberish, and needs a thorough overhaul so that a lasting solution is implemented.’

Dr Susan Hopkins, Public Health England’s incident director, said: ‘Although it may seem straightforward, there is no WHO agreed method of counting deaths from Covid-19.

‘In England, we count all those that have died who had a positive Covid-19 test at any point, to ensure our data is as complete as possible.

‘We must remember that this is a new and emerging infection and there is increasing evidence of long term health problems for some of those affected. Whilst this knowledge is growing, now is the right time to review how deaths are calculated.’

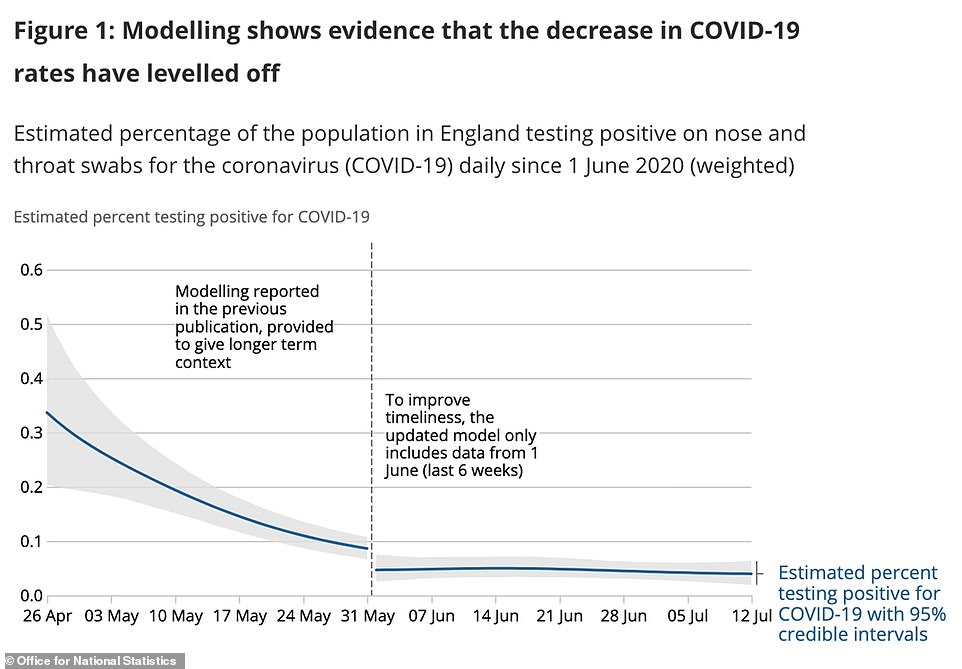

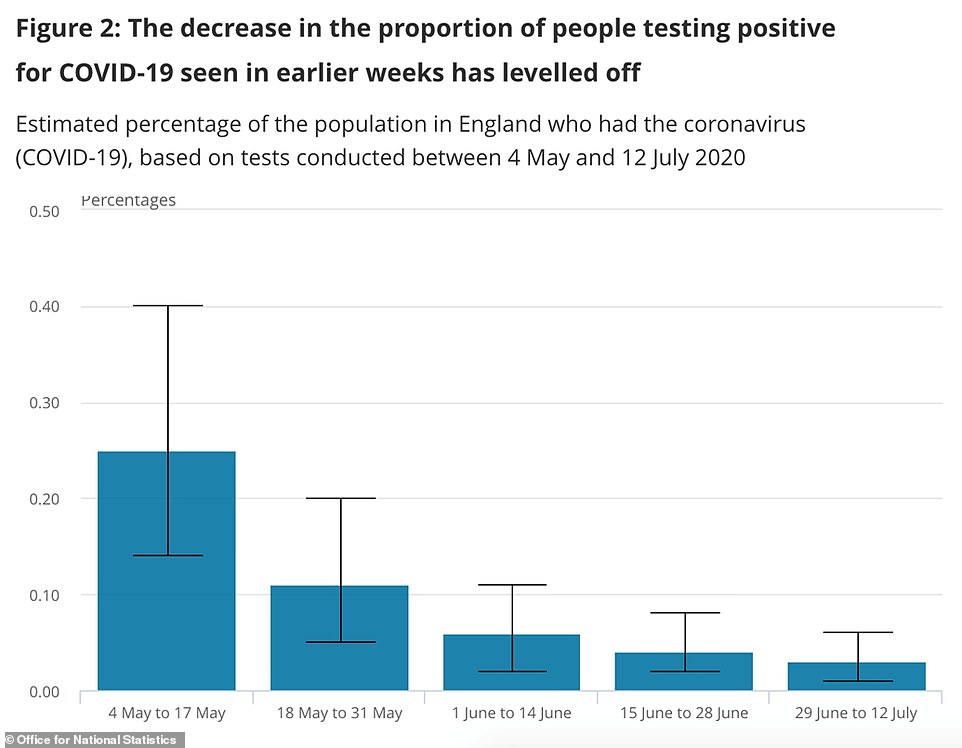

Other ONS data released today suggested the coronavirus outbreak in England isn’t changing in size and 1,700 people are still catching the illness every day.

Estimates based on population testing suggest one in every 2,300 people is now carrying Covid-19 – a total of 24,000 people or 0.04 per cent of the population.

This is a slight rise from the 0.03 per cent (14,000) estimated last week but both are within a possible range, showing any change is not significant.

The number of people catching the virus each day – 1,700 – has not changed in a week, however, and the ONS said the outbreak has ‘levelled off’.

Separate studies by King’s College London and Public Health England that estimate new cases suggest the range is somewhere between 2,100 and 3,300 – higher than that found by the ONS.

ONS data is considered to be some of the most accurate available – this week’s update was based on the results of 112,776 swab tests taken over six weeks, of which 39 were positive.

Separate antibody testing by the ONS – looking at people’s blood for signs of past infection – suggests that 2.8million people, or 6.3 per cent of people in England, have had Covid-19 already.

The ONS said it has today changed the way it counts data and is following trends over a six-week period rather than a two-week period. As a result it advises against comparing the new estimates to old ones.

Britain could ALREADY have herd immunity against the coronavirus because so many people have had similar illnesses in the past, study claims

Britain could already have herd immunity against Covid-19 because so many people have had similar illnesses in the past, a study claims.

Experts have noticed the infection looks extremely similar to other, milder strains of coronaviruses which cause coughs and colds and circulate regularly.

Brits who have had these in the past may have some level of ‘cross-protection’, they suggest, which means they aren’t seriously harmed by Covid-19.

While it remains unlikely that people will be totally protected from any infection at all, ‘background’ immunity could make their illness less severe and death less likely.

Theories that even exposure to common colds may protect people from the coronavirus have been floating around for months and raise hopes for a milder second wave.

Combined with the fact millions of people have been infected in the pandemic’s first wave, it may mean the UK is already protected against another deadly surge.

The concept of herd immunity – in which so many people are immune to a virus that it cannot spread – is controversial because there is no scientific proof that people who have had Covid-19 once can’t get it again.

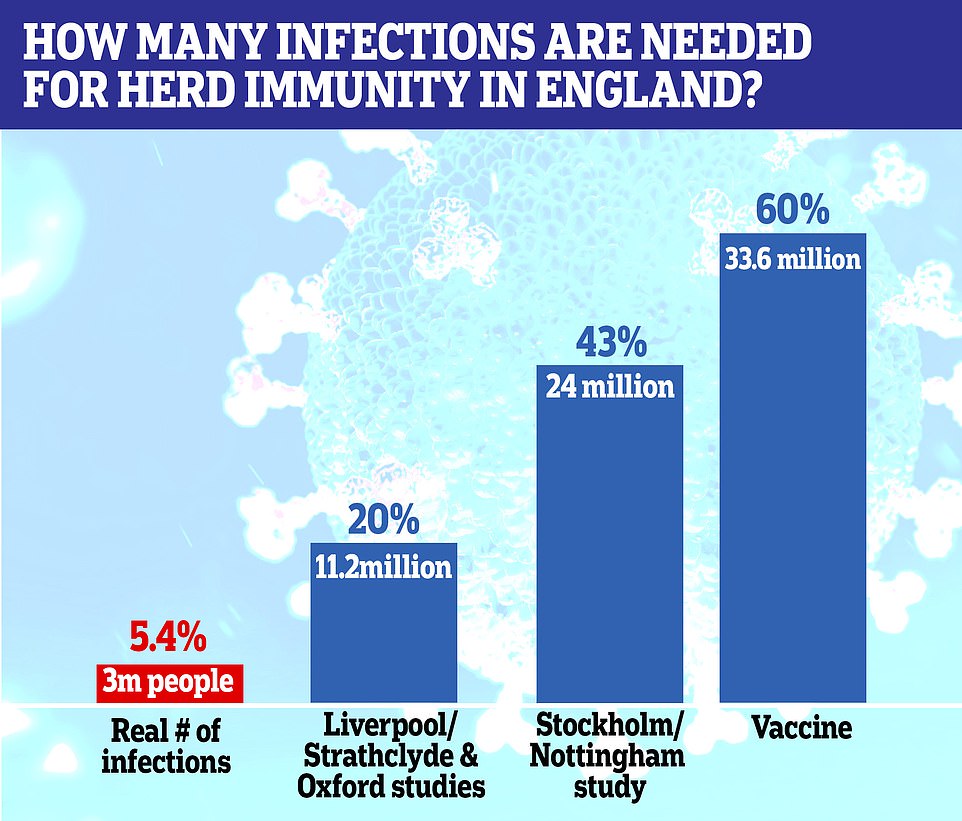

Scientists have claimed, however, that if immunity does develop, the proportion of people who need to have had it could be as low as 20 or even 10 per cent.

And Britain may already be reaching this level, the Oxford University paper said, adding: ‘[Immunity] measures of 10-20 per cent are entirely compatible with local levels of immunity having approached or even exceeded the [herd immunity threshold], in which case the risk and scale of resurgence is lower than currently perceived.’

Scientists say if a vaccine was developed it would need 60-70 per cent coverage to work — but this threshold could be significantly lower for natural immunity because the most at-risk people will always be the first to get exposed to the virus and, if it can’t infect them, it can’t spread through them to the less at-risk groups

A study by Oxford University said the threshold needed to achieve herd immunity could be lower than expected – scientists had thought it would be around 60 per cent if a vaccine was used – because coronaviruses are common.

There are four other types of coronavirus known to infect humans regularly, which are named NL63, 229E, OC43, and HKU1.

The fifth, known as SARS-CoV-2, is the one that causes Covid-19.

If people have had these in the past, their bodies may have developed some immunity to coronaviruses, the Oxford researchers suggest.

Professor Suneptra Gupta and colleagues wrote: ‘It is widely believed that the herd immunity threshold (HIT) required to prevent a resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 is in excess of 50 per cent.

‘Here, we demonstrate HIT may be greatly reduced if a fraction of the population is unable to transmit the virus due to innate resistance or cross-protection from exposure to seasonal coronaviruses…

‘Significant reductions in expected mortality can also be observed in settings where a fraction of the population is resistant to infection.

‘These results help to explain the large degree of regional variation observed in seroprevalence [how many people have signs of immunity] and cumulative deaths and suggest that sufficient herd-immunity may already be in place to substantially mitigate a potential second wave.’

The way cross-protection might develop lies in the fact that coronaviruses all have similar structures – that is, they have spike-shaped proteins on the outside.

These spikes may look similar to the body’s immune system and be recognised as a threat even if someone has not been infected with that particular one before.

When the body recognises a protein as a danger it can stoke the immune system into life and immediately send white blood cells and antibodies to destroy the viruses, thereby either preventing illness or making it less severe.

The body stores memories of how to fight viruses it has seen in the past and, if it encounters one that looks a lot like another one it has attacked, it may attack that more quickly than usual, too.

Immune cells are highly specific and only attack the bugs they are designed to, but if coronaviruses are extremely similar there is a chance that immunity developed to one virus may be compatible with another.

While this might not stop infection completely, the fast immune response could make the illness less severe and make it more likely that people will survive.

Research from scientists in Germany last month found that 81 per cent of people who had never even had the coronavirus produced some kind of immune response to it – which they put down to infection with common colds.

Researchers at the University Hospital Tübingen, who studied the immune reactions of 365 people, wrote: ‘Similarit

y to common cold human coronaviruses provided a functional basis for… immunity in SARS-CoV-2 infection’.

And Professor John Bell, another researcher at Oxford, recently said a significant number of people may have ‘background immunity’ to Covid-19.

He explained to MPs on the Science and Technology Committee that people were showing signs of a type of immunity called T cell immunity – T cells are ones that trigger the production of antibodies, which fight viruses.

Professor Bell said: ‘What seems clear is you do have cross-reaction from T-cells that are activated by standard endemic coronaviruses,’ The Telegraph reported.

‘I think they are present in quite a significant number of people.

‘So there is probably background T-cell immunity in people before they see the coronavirus, and that may be relevant that many people get a pretty asymptomatic disease.’

The Oxford team’s latest study – which did not involve Professor Bell – has not been published in a journal but on the website medRxiv without being reviewed by independent scientists.

In Britain’s first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, there have been almost 300,000 confirmed infections and 45,000 deaths.

Separate data suggests there have likely been more than 3.5million infections – most of them untested – and more than 60,000 fatalities.

Britain as a whole is not close to a high level of herd immunity, with Government testing surveys suggesting between five and six per cent of the population have had Covid-19 so far – about three million people.

London, however, has a much higher past infection rate at an estimated 17.5 per cent, so could be approaching a low level of protection.

The NHS is now preparing for a second wave of the disease but experts say they do not expect another one to be quite as devastating.

Future outbreaks will likely be confined to local areas and be able to be controlled with local lockdowns, they suggest.

While scientists around the world are racing to try and create a vaccine for the coronavirus, herd immunity may be vital as a long-term solution to the disease.

Sir Patrick Vallance, the UK’s chief scientific adviser, said yesterday: ‘It’s important to recognise that the chances of having a totally sterilising vaccine, i.e. one that 100 per cent protects you from this, I think, are low.

‘Much more likely that you have a vaccine that reduces the severity of illness and reduces spread a bit. I think that’s the more likely outcome on vaccines.’

Natural herd immunity – if lasting immunity develops from infection – can arise from the virus spreading through a large part of the population.

Immunity from a vaccine was expected to have to include at least 60 per cent of the population to effectively stop the virus from spreading.

But developing it through natural infection, meaning that the people most likely to spread the disease would get it first, may dramatically reduce that threshold.

A recent study claimed it could work to some extent if only one or two out of 10 people have been infected naturally and become immune to the disease.

They said higher estimates worked on the basis that immunity is given to everyone by a vaccine, but in reality the people who first get infected are likely to continue to be the ones most at risk, so if they develop immunity, the less-at-risk will also benefit.

These could include health workers, people who live in cities and those in people facing jobs like drivers, shop workers and schoolchildren and teachers, for example.

Immunity among the most socially active people, scientists say, could protect those who come into contact with fewer others.

The study led by Dr Gabriela Gomes, a mathematician at the Liverpool Schoo

l of Tropical Medicine and the University of Strathclyde, said: ‘In idealized scenarios of vaccines delivered at random and individuals mixing at random, herd immunity thresholds are given by a simple formula which, in the case of SARS-CoV-2, suggests that 60-70 per cent of the population would need be immunized to halt spread considering estimates of R0 between 2.5 and 3.

‘A crucial caveat in exporting these calculations to immunization by natural infection is that natural infection does not occur at random.

‘Individuals who are more susceptible or more exposed are more prone to be infected and become immune, which lowers the threshold.

‘In our model, the herd immunity threshold declines sharply… and remains below 20 per cent for more variable populations.’

Another study has taken a similar line and suggested herd immunity could develop at around 43 per cent of the population getting infected.

Professor Frank Ball, Professor Tom Britton and Professor Pieter Trapman — three authors of the study from the universities of Nottingham and Stockholm — wrote in the journal Science: ‘Our application to Covid-19 indicates a reduction of herd immunity from 60 per cent… immunization down to 43 per cent in a structured population, but this should be interpreted as an illustration, rather than an exact value or even a best estimate.’

They said that immunity would be stronger in cities, large households and big workplaces.